Parents may reduce a high level of work-family conflict by cutting back paid employment hours or giving up their supervisor/management status, the latest Melbourne Institute report into Australian family life has found.

The report, Living In Australia 2019, is a new publication which integrates with the long-running annual HILDA survey – HILDA standing for Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia. Started in 2001, HILDA tracks trends in daily living for Australians (see notes at the end of this article).

The new Living In Australia 2019 findings are particularly valuable reading for anyone working with Australian families – including those in the early childhood education sector.

Work-family conflict

One of the key areas for ECE readers from the report is a chapter describing the scale and impact of conflict that parents feel between their working roles and their family life.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is mothers in full-time work who feel the greatest conflict and are least able to find ‘balance’ between their desire to be present for their families and their responsibilities in paid work.

“Not only have mothers’ working hours increased since 2001,” the report says, “[but] full-time working mothers, on average, also express a significantly higher degree of difficulty in balancing work and family life than is the case for all parents.”

Older may be harder

The very early years of parenting – when children are three years old or less – can be perceived as more stressful for families. These are the years when adult sleep is most disrupted, when new routines are constantly emerging, and when new parents may be most concerned about developmental stages and childhood illnesses.

However, the Melbourne Institute finds that parents with children aged birth-three years old experience the least overall conflict in work-family balance. They point to the typically lower number of hours worked by at least one parent during that time.

“Mothers with young children (aged 0 to 3 years) report relatively low levels of work–family conflict, which is partly explained by their concentration in part-time jobs,” the report says.

Fewer hours, lower status

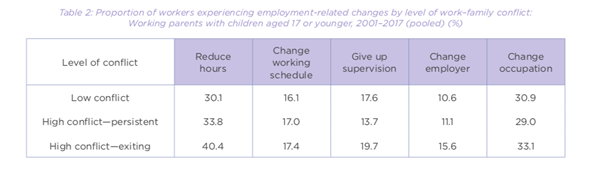

The Living In Australia 2019 researchers are drawing from the long-term annual findings in the HILDA survey, which allows them to draw some conclusions about work-family conflict that aren’t available in one-off studies. In this case, the researchers looked at what had changed for people who reported a high level of work-family conflict in a previous survey year, followed by a lower level of conflict in the following year (see table below).

Source: Living In Australia 2019

Source: Living In Australia 2019

“A reduction in the number of hours worked from one year to the next, a change in working schedule, or giving up a supervisory role seem to decrease the level of work–family conflict for those who are employed,” the report says.

The outcomes for women may include embedding professional pay inequality by stepping out of a management career path. Taking a cut in hours, while potentially beneficial for family life, may be detrimental to family income, ability to pay bills and, of course, personal contributions that a woman makes to her superannuation.

This scenario has an even greater impact when, as is the case in nearly one-in-four dual income male/female relationships, the woman earns more than her male partner.

“Over the past 17 years, there has been an increase of two percentage points in the proportion of couples in which the woman earns more annually than the man, from 22 per cent in 2001 to 24 per cent in 2017,” the report says.

Fee increases

The report includes a Spotlight on child-care [sic] costs that describes increases in fees tracked across Australia over the 15 years from 2002-03 to 2016-17. The high figure in one of those measures (see table below) has attracted considerable media coverage and you may have seen it mentioned elsewhere recently.

| December 2017 prices |

2002-03 |

2016-17 |

% change |

| Median weekly expenditure |

$62 |

$153 |

145% increase |

| Median expenditure per hour of child care |

$4.10 |

$6.20 |

51% increase |

Source: Living In Australia 2019

Media reports have focused on the 145% median increase in family expenditure on ECE fees – and as is often the way this has been shorthanded to ‘fee increases’. This is not what the report shows. The increase in median weekly expenditure on ECE from $62 to $153 is, the report acknowledges, “in part…the result of increased uptake of child- care services”.

In other words, expenditure has increased because more Australian families are using ECE for more of their children.

The more relevant figure for increased fee costs is in the third row of the table, where the per hour median price paid in 2002-03 was $4.10 and in 20016-17 had risen by 51% to $6.20.

Stresses continue

While the cost of fees in family expenditure remain a major source of stress in the HILDA survey, the Living In Australia 2019 report also features two other major causes of stress relating to children’s care for working parents.

“Over the past few decades, child care for children not yet in school has become a major concern among Australian families who struggle to balance their child care responsibilities with paid work outside their home,” the report says.

The top three causes of stress are:

- Financial cost of child care

- Finding care for a sick child

- Finding care at short notice.

Food for thought

The findings in this first Living In Australia report for early childhood education professionals raise food for thought, and some of these questions may be worth raising at your next staff discussion:

- While they can look more confident, are parents of older children under more stress from work-family conflicts than parents of infants and toddlers?

- Is there anything our service could do differently to help resolve work-family conflicts before women take the more drastic action of cutting their paid employment or stepping out of a senior workplace role?

- How much has our hourly fee changed since 2002 (if known)? And how does that compare with changes to our salaries and changes in the economy of the community we serve?

- Is there anything in our answers to these questions that we could share with our local politicians or the local media to improve understanding of early childhood education?

Notes on the source report:

Commenced in 2001, the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey is a nationally representative household-based panel study, providing longitudinal data on the economic wellbeing, employment, health and family life of Australians. The study is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services and is managed by the Melbourne Institute at the University of Melbourne. Roy Morgan Research has conducted the fieldwork since 2009, prior to which The Nielsen Company was the fieldwork provider.

Read the full Living In Australia 2019 report here.

Meet the author

Bec Lloyd is the founder and managing director of Bec & Call Communication, providing professional writing, editing and strategy services to the school and early childhood education sector since 2014. In 2018 she launched UnYucky mindset and menus for happier family mealtimes. Formerly the communications lead at ACECQA and BOS (now NESA), Bec is a journo and mother of three who produces Amplify for us at Community Early Learning Australia.