By Kathryn Albany, Early Childhood Teacher (preschool room), Explore and Develop, Lilyfield

In early 2019, educators at our long day care centre decided that we wanted to celebrate family diversity. This was partly to represent the different families in our centre, however we also wanted to model inclusion for all children and families. This is because inclusion is beneficial for all children, not only those who may face discrimination or exclusion (Cologon & Salvador, 2016).

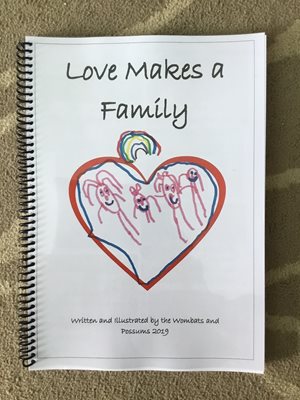

The two preschool teachers decided to base our project around Mardi Gras. Our project came to be called ‘Love makes a family’ and has been part of our program ever since, across two preschool rooms in this centre, involving children from two to four years. We believe this project could be a template for inclusive practice in other preschools, as well as an example of how socially just pedagogy can impact on the broader community.

While it may seem controversial to introduce LGBTIQ+ families into preschool, it is crucial to remember they are already here (Rawsthorne, 2010; Skattebol & Ferfolja, 2007). Rather than insisting that families should conform and become invisible, we wanted to ensure that all children can be proud of their unique family structures (Skattebol & Ferfolja, 2007).

Some parents may fear that we would have uncomfortable or inappropriate conversations about sexuality, however in reality we can speak about family without reference to sexual activity, just as we do for every other family type (Chng, 2017). Social justice requires us to take brave choices to further equality in our classrooms and broader society, and after some reflection and discussion, we didn’t find this was ‘brave’ at all; this was necessary.

Extensive research shows that children from same-sex parented families develop on par with children from heterosexual families (Averett, Hedge, & Smith, 2015; Bos, van Balen, & van den Boom, 2005). However, children from these families can still face discrimination and backlash (Gunn & Surtees, 2011).

In our classrooms, we have children from diverse family types such as mother/ father families, single mother families, two mother families, families where grandparents are caregivers, and families where there is mental illness or physical disability. In addition, there are children who were born through IVF and other assisted reproductive technology such as surrogacy, regardless of their structure. We know that in the broader community there are families with adoptions, foster care and kinship arrangements, amongst many others.

Our goal with this project was to encourage children to see the wonderful love that exists in their family, whilst recognising that this love is the (only) common thread that exists in families. We wanted to explicitly teach children that it is family function rather than family structure that is important (Taylor, 2006).

We began by talking to the children extensively about families.

They shared a range of opinions about what makes a family:

“I love my family” said Laila, while Harrison said “It means you love your family so much!”.

Ollie said “If you love your family, they’re your family”.

Alice noted that “Some people have one dad, or two dads or two mums” and Noah agreed “The two mums look after you if you don’t have a dad”.

Ollie added “If you have two mums and two grandmas, you have a lot of love”.

“There’s one mum and one dad in my family. We play with each other” said James. (excerpt from documentation 7.3.19)

Some texts that challenge gender-normative and hetero-normative biases which we used in the classroom

Some texts that challenge gender-normative and hetero-normative biases which we used in the classroom

To build on their understandings, we introduced a wide range of books that depicted a range of families including LGBTIQ+ families. We critically reflected on the books in our room and had explicit conversations about bias in books (Taylor & Richardson, 2005). The children began to draw their families, and this led to our project idea: creating a book with pictures and quotes from every preschool child.

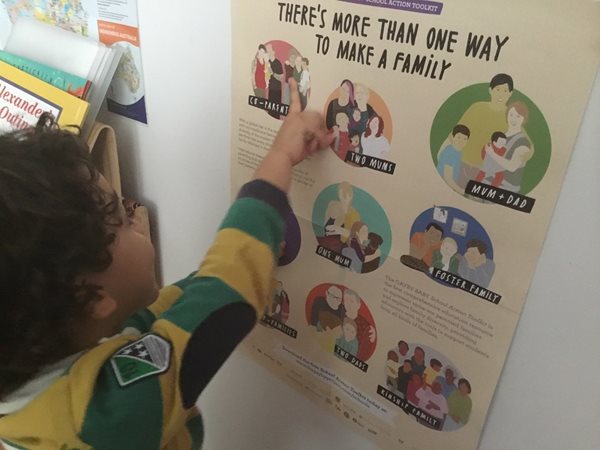

As well as the children’s pictures, we included resources such as the “There’s more than one way to make a family” poster from the Gayby Baby team.

As well as the children’s pictures, we included resources such as the “There’s more than one way to make a family” poster from the Gayby Baby team.

Over a few weeks (and in time for Mardi Gras) we were able to sit with every child to discuss families while they drew a picture using textas. A template was used with the words “love makes a family” and a large love heart frame to tie every work together and to reinforce the message we were trying to convey.

We asked the children questions like “How do you show you love your family?” or “What do you love to do with your family?” and “What is love?” to guide these discussions and wrote down their responses. We then collated the pictures and wrote up their quotes. These were bound into books available for children, families and educators to look over.

This project was overwhelmingly well received by families and children. Children seemed to enjoy the opportunity to represent their unique families through drawings and their quotes. Families came and spoke to us about how much they loved the work we were doing with children. Educators commented on what a great project this was.

This project was overwhelmingly well received by families and children. Children seemed to enjoy the opportunity to represent their unique families through drawings and their quotes. Families came and spoke to us about how much they loved the work we were doing with children. Educators commented on what a great project this was.

We did have one parent ask us to stop talking about LGBTIQ+ families with all children. This parent’s concerns were acknowledged and reflected upon. The teachers and director composed a response, stating that we would continue to advocate for inclusion. This was a powerful moment; it did feel a little revolutionary. As teachers, we did reflect on the work of Freire and his idea that teaching is a political act with the capacity to transform society (Freire, 1972; Friere, 2014 (1994)). Remaining neutral was not an option, as it simply reinforces the status quo and discourages what can be seen as difficult discussions with young children (Chng, 2017; Robinson, 2015). Children from diverse families are not ‘the same’, indeed the literature describes a need to be seen as ‘different’ (Hosking, Mulholland, & Baird, 2015). However, they do deserve to be treated equally, and to see their family accepted as they are; neither perfect nor deficient.

The finished product is a beautiful book that we can share with families and our community. The outcome of the project was a confidence that we are benefiting all children in our care as well as advocating for a fairer society. We wanted to share this project with other educators in the hopes that it might provide a template for other early childhood educators to follow, either with family inclusion or other types of inclusion. Though it can seem daunting, the conversations generated by this project have improved inclusion in our centre and provided educators with the confidence to keep working towards our anti-bias goals in a range of areas.

This joint project was planned and implemented by Kathryn Albany, Monica Barba (ECT in the 2-3yrs room) and Catherine Sansom, the Educational Leader at Explore & Develop Lilyfield.

- References

Averett, P., Hegde, A., & Smith, J. (2015). Lesbian and gay parents in early childhood settings: A systematic review of the existing research literature. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 1-13. doi:10.1177/1476718X15570959

- Bos, H. M., van Balen, F., & van den Boom, D. C. (2005). Lesbian families and family functioning: An overview. Patient education and counseling, 59, 263-275. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.006

- Chng, A. (2017). Diving into the unknown: the experience of pedagogical documentation at Mia Mia. In Pedagogical documentation in early years practice (pp. 147-158). London: SAGE.

- Cologon, K., & Salvador, A. (2016). An inclusive approach to early childhood is essential to ensuring equity for all children. In C. G. Development (Ed.), Global report on equity and early childhood (pp. 51-76). Netherlands: International Step By Step Association. Retrieved from http://www.ecdgroup.com/cg2/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/CGGlobal-FullReport-English- R2-WEB-LowRes.pdf

- Gunn, A. C., & Surtees, N. (2011). Matching parents’ efforts: how teachers can resist heteronormativity in early education settings. Early Childhood Folio, 15(1), 27-31. Retrieved from https://www.nzcer.org.nz/nzcerpress/early-childhood-folio

- Hosking, G., Mulholland, M., & Baird, B. (2015). “We are doing just fine”: The children of Australian gay and lesbian parents speak out. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 11(4), 327-350. doi:10.1080/1550428X.2014.988378

- Rawsthorne, M. (2010). Mother impossible: The experiences of lesbian parents. In S. Goodwin, & K. Huppatz. (Eds.), The good mother: Contemporary motherhoods in Australia (pp. 195-213). University of Sydney, NSW: Sydney University Press.

- Robinson, K. (2005). Doing anti-homophobia and anti-heterosexism in early childhood education: moving beyond the immobilising impacts of ‘risks’, ‘fears’ and ‘silences’. Can we afford not to? Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 6(2), 175-188. doi:10.2304/ciec.2005.6.2.7

- Skattebol, J., & Ferfolja, T. (2007). Voices from an enclave: lesbian mothers’ experiences of child care. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 32(1), 10-18. Retrieved from http://www.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/our-publications/australasian- journal-early-childhood/

- Taylor, A., & Richardson, C. (2005). Queering home corner. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 6(2), 163-173. doi:10.2304/ciec.2005.6.2.6

- Taylor, J. (2006). Life chances: Including the children’s view. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 31(3), 31-39. Retrieved from http://www.earlychildhoodaustralia.org.au/our-publications/australasian-journal-early-childhood/