A while back I saw an Instagram post by an Aboriginal mum who was in the process of searching for a day care service for her child. She had posted on her Instagram page, questioning why she had needed to visit at least eight centres before she had found one that clearly implemented Aboriginal perspectives into their curriculum.

There were two key points that this mum highlighted in her post:

- Many centres did not seem to have fundamental understandings of relatively commonplace Aboriginal practices. For example some had told her that they did a “Welcome to Country” everyday (obviously meaning an Acknowledgement to Country as Welcomes can only be performed by Traditional Owners or those with permission to do so on that particular country).

- Many services seemed to display or use Indigenous “inspired” resources (resources that are not made by or in partnership with Indigenous people or businesses, which are in fact “fake” Indigenous art and resources). It seemed that the inclusion of Indigenous “elements” into the classroom were piecemeal and often lacked clarity around how they could support a child's learning and understanding.

This got me thinking, if a parent is able to ascertain such a level of cultural incompetence in just one introductory visit to a centre, then it must be indicative of a deeper problem in those particular centres, where cultural capability is at worst, non-existent, or at best, not visible. As an Aboriginal mum myself, I don’t think a parent should have to dig too deeply to find out how a centre is incorporating First Nations culture into their classrooms respectfully, and engaging their children in this type of learning.

In a previous article I wrote which covered the topic of supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families of children with disability, I mentioned the term "visibly culturally capable". By this I was referring to the degree of cultural capability that a service was demonstrating to their First Nations families. Just like the mother I mentioned earlier, who could tell straight away that a centre was not culturally capable and was not going to be suitable for her children, it should be evident just as quickly that a service IS culturally capable.

So what does it actually involve to become “visibly” culturally capable?

Without getting too caught up in the jargon, it essentially means that when a person enters your centre, be it families, community members, or the children attending themselves, they are met by clear and visible actions that demonstrate your centre's commitment towards actively including Indigenous Australia into their service in respectful and authentic ways.

The term “ally” is often used nowadays to describe a non-Indigenous person who uses their position to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities in ways that avoid paternalism and cultural appropriation. I believe that this is what services should be striving to achieve; to demonstrate to their families that they are an “ally”.

Summer May Finlay, a Yorta Yorta woman, academic, writer and public health consultant wrote a brilliant article for Reconciliation NSW on what it means to be an ally. She outlined the following seven steps to becoming a “good ally”. These seven steps can be very effectively applied to the early childhood education space to provide insight on how services can become ‘visibly culturally capable’:

1. Preference our voices

“Don’t speak on our behalf. We have a voice, and we aren’t afraid to use it," writes Summer.

Actively seek ways to include the voices of Indigenous families and communities in your service, be it through incursion / excursion, RAP development, curriculum input.

2. Be OK with not always being part of the conversation

“As Aboriginal people, at times yarns may be off-limits to non-Aboriginal people for many reasons.”

This comes back to understanding that cultural protocol exists and it is important to take the time to find out what these protocols are in your own local community context.

3. Be there for the good times and the bad

“This requires taking an active interest in our issues rather than just having a NAIDOC morning tea or romanticising Aboriginal dreaming stories. As Aboriginal people, we don’t have the option of picking and choosing when we can be Aboriginal. Our allies need to stand with us, even when the going gets tough.”

This comes back to tokenism and truth-telling in the classroom. Diverse Indigenous content needs to be included regularly and not just at special times of the year such as NAIDOC week. It’s also important to ensure that the more difficult issues are not ignored or silenced, within an age-appropriate context. The Black Lives Matters movement is a good example. Sometimes this may not mean addressing the content with your children, but rather, engaging your staff in learning around these issues, which no doubt impact on First Nations families who attend your service.

4. Say something when you hear someone say inappropriate things about Aboriginal people.

This one speaks for itself. As role models for our kids, educators need to be strong enough to take a stand.

5. Don’t take it personally when we don’t agree with you.

“Understand that a good ally can sometimes be wrong on issues affecting Aboriginal people," writes Summer.

This is about taking opportunities to educate ourselves and our staff and colleagues. No one can be expected to know everything and get everything "right". In the education space, we often see Indigenous content put in the ‘too hard’ basket for fear of getting it wrong. It's better to be made aware of wrong actions or mistakes, and take steps to correct our information for the future, than deny children access to the wide breadth of knowledge Indigenous Australia has to offer. A good ally accepts that they will make mistakes, doesn’t take it personally, listens to Indigenous voices and takes more informed steps in the future.

6. Don’t go it alone

“Don’t assume you have enough information or experience to march ahead without stopping to check with Aboriginal people that you are heading in the right direction.”

Again, this comes back to Indigenous input. Connecting with our local families and communities is essential.

7. Understand that Aboriginal people are *not* all the same

“We do have different views, just like other Australians.”

This diversity needs to be reflected in your classrooms through learning content and resources.

(Source: Reconciliation NSW: Being an Ally by Summer May Finlay, 2019)

An ongoing journey vs. ticking boxes

It is important to remember that visibly demonstrating cultural capability in your service should be viewed as an ongoing learning journey rather than a goal to achieve or a box to tick. It’s ok to start small, and go from there.

“There are simple things that Early Childhood Centres can do to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture is visible and valued within their centre; the most basic being displaying the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Flags proudly and prominently,” says Katie Dalton, an Aboriginal primary school teacher.

“Centres need to ensure their play and learning spaces are culturally inclusive by ensuring that First Nations people are represented through the use of dolls with different skin shades and features, through the imagery used and the stories.

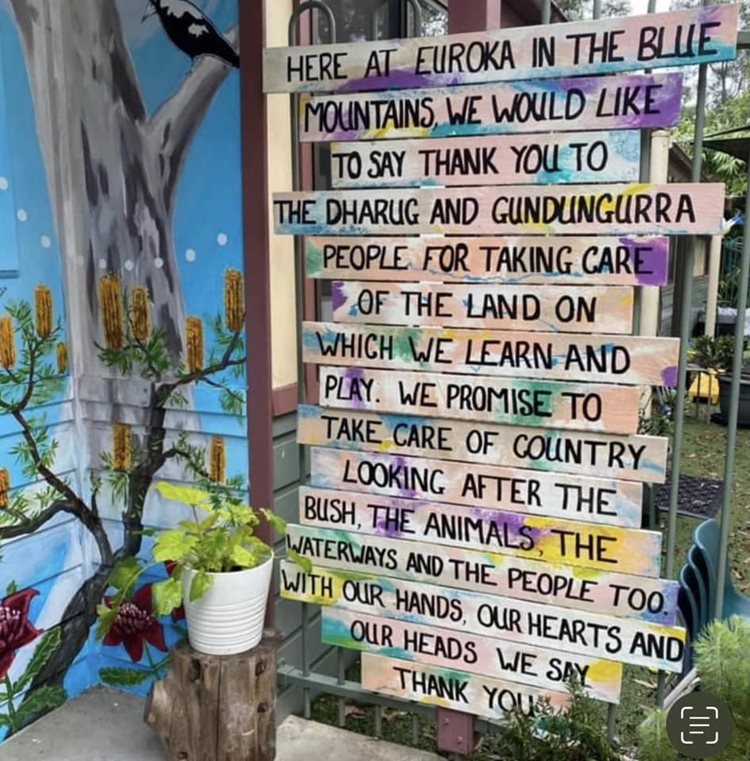

“Displaying decor with Aboriginal design, made by Aboriginal artists, will support the visibility of culture and help our families feel more comfortable in the space. The simple step of having an Acknowledgement of Country marked at the door upon entry helps families to feel seen, welcome and valued.”

Acknowledgement to Country at the entrance to Euroka Children's Centre. Image via Euroka Children's Centre.

Moving beyond these surface actions, services can consider cultural capability training to equip staff with the background knowledge, communication skills and foundations needed to take those steps towards becoming a good ally. In the early stages of your journey, this may seem like a daunting thing to think about, but it need not be when approached with an open heart and mind. Ultimately, an early childhood centre that is actively striving to demonstrate cultural capability is one which will provide our children with immense educational and lifelong learning benefits as they themselves grow and engage further with these issues in society.

Further reading:

Reconciliation NSW: Being an Ally by Summer May Finlay

Queensland Government, Child Safety Practice Manual: Being culturally capable and responsive

Amplify! Championing reconciliation through art by Deborah Hoger

Amplify!: How to conduct a bookshelf audit by Deborah Hoger

Amplify!: Avoiding the trap of cultural tokenism by Deborah Hoger

CELA training relating to this topic

FIND OUT MORE

FIND OUT MORE