Strengths-based language focuses on a person's abilities, talents, and resources, rather than their challenges. It can foster positive self-esteem, motivation, and resilience, promoting more effective personal development and progress.

Adopting strength-based language in our planning and programming is commonplace. Yet, it can pose a unique challenge when applied to conversations with families.

“Why do we have to sugarcoat everything?”

“Can’t we just call a spade a spade?”

“Not everything is a strength!”

These are things we hear all the time when discussing the importance of strength-based language with families in the early years. I’m not going to pretend that using strength-based language is always easy—it's truly an art. Like any art form, it may take years to master and is typically only recognised by fellow practitioners.

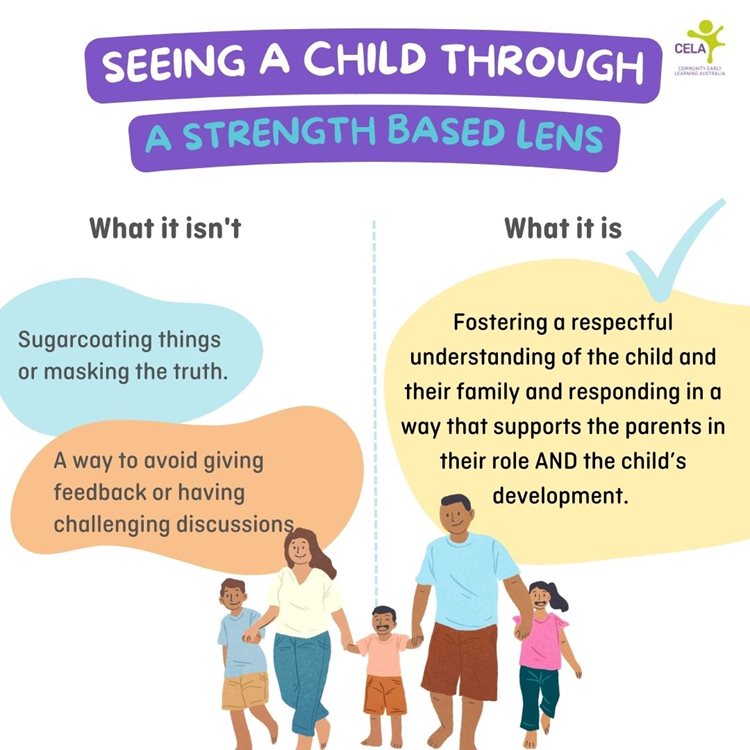

Seeing a child through a strength-based lens isn’t about sugarcoating things or masking the truth.

It’s about fostering a respectful understanding of the child and their family and responding in a way that supports both the parents in their role and the child’s development.

Strength-based language as a tool

We often talk about using intentional teaching as a tool. It’s something we put into practice when required, tweaking it to meet the needs of a specific group of children. For some children, we might deliberately foster a scaffolding approach, encouraging them to build their learning experiences with a peer. For others, our teaching may be more direct, posing leading questions and encouraging them to persist amidst challenges.

This is not dissimilar to using strength-based language in our interactions with families. It’s a tool that we have at our disposal, particularly when having challenging discussions.

The messages we give parents are important and often dictate their response to us

We often forget that parents are on a journey too. They may lack understanding about child development and have no training in how to respond to challenging behaviour or identify atypical development. This is where our expertise comes into play. We need to utilise our knowledge to support parents in understanding their child's needs and how best to support them.

_________________________

Years ago, I had a family attending my service who were really challenged by the behaviour of their middle child. I had also seen some challenging behaviours (her favourite was to slap me on the bum and run away), which I interpreted as that child’s way of reaching out for connection and friendship. The dad was honest with me in his struggles, each day commenting how the morning had been a challenge, or that she had been rough with the younger sibling and so on. One morning, the comment was simply “Good luck with her”.

Despite these behavioural challenges, I discerned unmet needs within this child. Instead of fuelling the negative perception surrounding the child, I reframed the behaviour. My responses to the dad transformed into positive phrases such as:

She really loves you, it’s so nice that she would do that to spend time with you.

_________________________

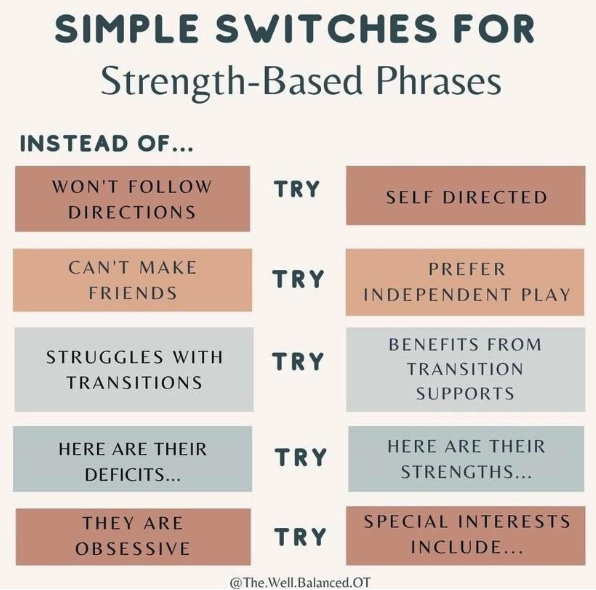

Behaviour is separate to a child. When we label the child as “not listening” or someone who “can’t make friends,” we're endorsing the negative narrative about the child. When we separate the child from the behaviour, we can see that there are skills still under development. In my experience, parents are generally receptive to discussing ways we can enhance their child's skills.

For a child that is still learning how to interact with peers, you might suggest ideas like, “Nelly might benefit from some more play dates with children in the group, so she can build these skills in a setting where she feels most comfortable”.

- Does a child constantly snatch toys? We need to build impulse control.

- Does a child frequently dictate play? Make it clear that they’re still building the skills necessary for empathy.

- A child refuses to try and sit on the toilet? They’re still building self-confidence and a sense of belonging in the setting.

When we discuss these challenges with families, it’s OK to acknowledge that the child needs support in an area. However, it’s our role to support the child and their family in building the skills which may be lacking. Sometimes that may be sending a particular book home for the child to read with their parents (for example, a book discussing the concept of being a kind friend).

At other times, we may recommend a hearing test or a speech therapist to evaluate a child’s ability to hear, comprehend, and respond to others. Offering a solution or support to address these areas is a great way to follow a strength-based approach. There's no advantage in identifying a problem without offering any guidance or assistance.

The importance of getting to know the family

Every family is different. Some families will be open to feedback, others will not.

Recently I had a parent join us for a “stay and play” session at the preschool where I teach. Throughout the session, her child was boisterous, lively, and somewhat disruptive. At the end of the session, she asked me if that behaviour occurred regularly. I confirmed that it did, but that loud and sometimes disruptive behaviour was only one small aspect of her child. I pointed out that he was also very warm, social, inclusive and empathetic and had incredible interpersonal skills. I was able to discuss that although he didn't always engage in structured learning, he was incredibly skilled at extending his own learning and relating to others.

Focusing my communications on strengths paved the way for discussions about how we can develop certain skills, and the family recognised that I was not judging them.

Other families may respond better to a gentler approach. You may need to inquire if their child has had their hearing checked, as they often don’t respond to directions from educators. Presenting an example can bring up the concern more gently.

You might say, “I've observed that when we call the group to come inside, [child's name] tends to run off”. This technique portrays the behaviour as situational, instead of being a defining characteristic of the child's personality.

It’s important to give a range of feedback, both positive and strength-based, about a child’s progress. Even when there are challenging behaviours, progress is still likely to be occurring in certain areas.