Micromanagement is the antithesis of modern management practices that seek to empower employees and delegate decision making through the organisation. Characterised by close oversight and excessive control, micromanagers can leave a trail of frustration and burn out in their wake.

This is especially true in early childhood education and care, where micromanagement can stifle creativity and curiosity, minimising a team member's autonomy to do their job well.

The psychology of a micromanager

Researchers have found that a person’s willingness to delegate decision making is impacted by their sense of psychological power, i.e., the amount of influence they feel they have over their environment. The lower a sense of one’s psychological power, the less likely they are to delegate.1

Micromanagers can operate from a place of insecurity or anxiety, leading to behaviours that are counterproductive to fostering a supportive and empowering work environment. In the early childhood education and care sector, this may be linked to a pressure managers feel to maintain regulatory compliance and meet parent expectations.

The toll of micromanagement

Employees who are micromanaged are more likely to feel stressed during their workday.2 They’re also more likely to report decreases in both morale and productivity.3

Barbi Clendining, Co-Founder of FireflyHR, says that micromanagement can breed gossip and toxicity that casts a shadow on workplace dynamics.

“Employees may feel disempowered, lacking a sense of ownership and direction,” she adds. “They may feel like they don’t have a say in decision making and no genuine opportunities to provide feedback.”

The implications of micromanagement for morale and productivity are serious. But so too are the impacts on educator autonomy, confidence and motivation. Innovation and creativity are stifled. Educators are unable to make the important decisions they need to adapt to meet children’s unique needs. At a service level, quality suffers, achieving the opposite of the micromanagers desire.

Identifying a micromanager in early education

In a sector where policies and procedures play such an important role in supporting quality practice, Barbi cautions that this can make the task of identifying micromanagement even more challenging.

“Is it micromanaging? Is it a policy? Is it a practice due to a regulation or something identified in the quality improvement process?”

To identify micromanagement, some signs to look out for include:

-

excessive scrutiny of lesson plans, classroom management and interactions with children

-

a focus on minor details, such as the colour of a worksheet, while overlooking the bigger picture, such as the quality of the curriculum.

-

constant interruptions throughout each day to offer unsolicited advice or direction

-

disregarding feedback and suggestions when making decisions

-

difficulty in delegating tasks to others and taking on too many responsibilities for themself

-

frequent changes to policies and procedures without consultation.

Navigating micromanagement

There’s no doubt that working with a micromanager can be stressful and frustrating. But it doesn’t have to be a completely hopeless situation. The key is addressing the situation directly through clear communication and a solutions-oriented approach.

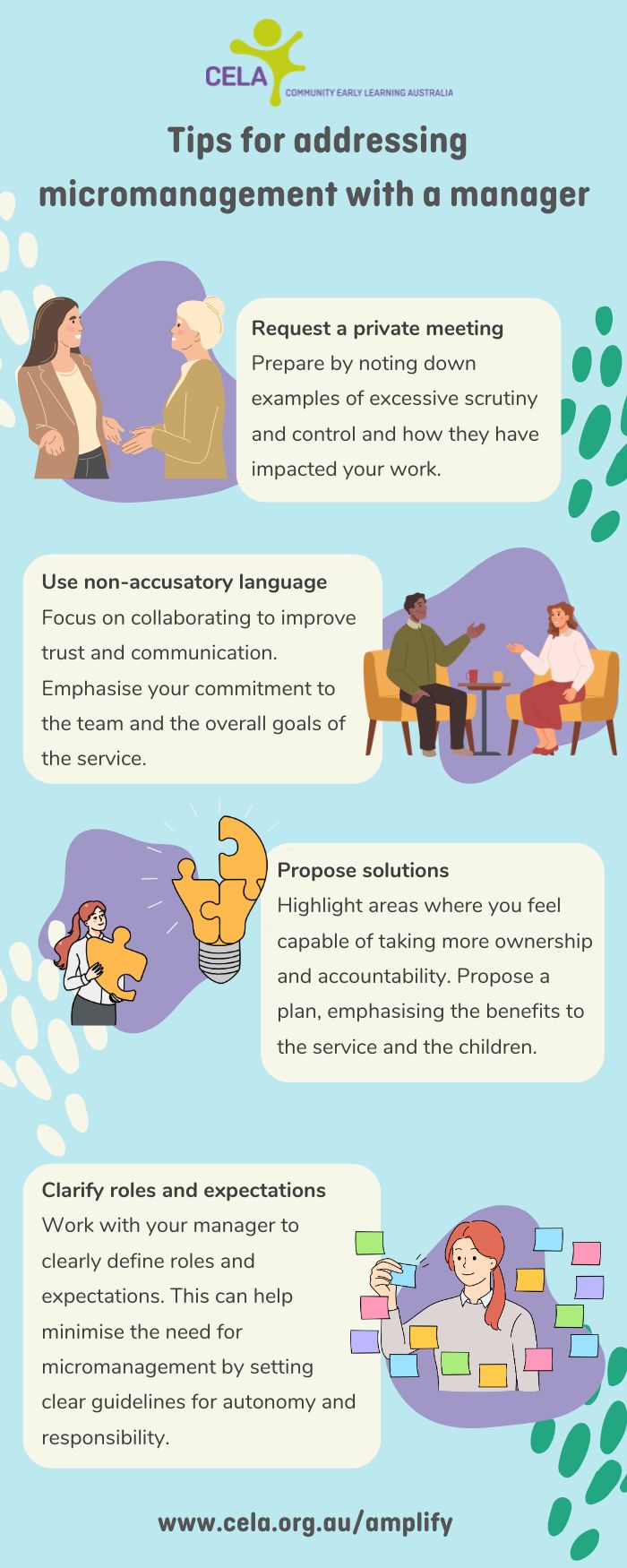

Start by requesting a meeting. Prepare for the meeting with specific examples of scrutiny and control and how this has impacted you and others. Avoid accusatory language and emphasis that you’re focused on collaborating to establish trust.

Highlight to your manager where you feel you can take ownership and accountability, and propose a plan for moving forward. If your manager becomes tense, bring them back to how this will benefit the service and the children.

Barbi says that open dialogue and addressing concerns is key.

“Clearly defined roles and expectations can help to minimise micromanagement,” she explains. “So too can fostering a culture that encourages autonomy and independent decision making. In some cases, micromanagement can be solved with professional development in areas such as delegation.”

A distributed leadership model, such as at Euroka Children’s Centre, can also prevent micromanagement from occurring.

“After some reflection, I realised that creating a leadership team potentially marginalised others in the team,” says Director Lorriene Bullivant. “It created a ‘them and us’ scenario, which was certainly not our intention.”

She says that under the distributed leadership model, “everyone is heard and has the opportunity to grow as a professional.”

Tips for team members: How to address micromanagement with a manager

Tips for management: How to resolve micromanagement issues in your service

Promote a culture of autonomy: Advocate for a workplace culture that encourages autonomy and independent decision-making. This can reduce the perceived need for constant oversight.

Facilitate professional development: In some cases, addressing micromanagement may involve professional development, particularly in areas such as delegation. This can help both managers and employees better understand how to balance oversight with autonomy.

Consider a distributed leadership model: Explore the possibility of adopting a distributed leadership model, which can prevent micromanagement by ensuring everyone's voice is heard and valued. This model encourages professional growth and reduces hierarchical divisions within the team.

References

-

Haselhuhn, M. P., Wong, E. M., & Ormiston, M. E. (2017). With great power comes shared responsibility: Psychological power and the delegation of authority. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.052

-

American Psychological Association (2023). 2023 Work in America Survey.

-

Harvard Business Review (February 2020). How to stop micromanaging your employees.

About CELA

Community Early Learning Australia is a not for profit organisation with a focus on amplifying the value of early learning for every child across Australia - representing our members and uniting our sector as a force for quality education and care.